Galaxy Classification

Contents

Serendipitous finds

Spitzer's cameras have relatively large fields of view (for infrared cameras), and Spitzer is really efficient at covering large areas of sky. Thus, it is often the case that sources are serendipitously imaged -- for example, galaxies caught in the background of an image of something else. You can do science with these objects.. science that the original astronomer who got these data is not likely to have done!

On the right is an example of just such an image. The picture is meant to be of the planetary nebula in the center (original press release), but the galaxy in the upper right was caught by accident. The people who took this picture wanted to study the planetary nebula. They didn't care about the galaxy in the background.

Things to do with these galaxies

In this case, you can clearly see spiral arms. Here are some things you can do with galaxies you find in Spitzer images.

- Classify them. Start by going to Galaxy Zoo, learn about galaxy classification, and train your eye on how to recognize shapes of galaxies.

- Is the classification the same in the infrared as it is in the optical? Not necessarily! Go to, for example, Skyview and grab an optical image (or from any other wavelength for that matter) and see if you get the same classification.

- Are you the first person on the planet to think about this galaxy? Go to NED, the NASA Extragalactic Database, and search (by position is probably easiest) to see if anyone else has studied this galaxy before. Did they get the same classification as you did? What else do they know about this galaxy? Do you know something now that they don't know? (Has anyone published anything on Spitzer data yet?)

- How big is it in pixels, arcseconds, or (if you have a distance to the galaxy from NED) light years (or parsecs)?

- Does it have any friends nearby? Galaxies, like stars -- or teenagers -- usually tend to come in groups... where you find one, another one is usually not too far away. How far away is it from its friend? Is there any evidence that the two galaxies are close enough to interact with each other?

Spitzer's spatial resolution

Despite the example above, where you can clearly see spiral arms in the galaxy, not every galaxy is so lucky.

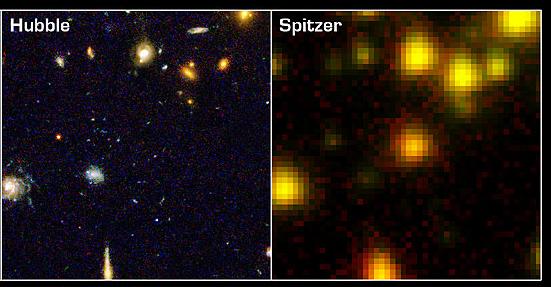

In the picture on the right (taken from this press release), you can see a (small) patch of sky imaged with Hubble (left) and Spitzer (right). The original point of this image was to show how phenomenally sensitive Spitzer is - there is a thing in the center of the frame that is not seen by Hubble, but Spitzer clearly shows that it is there. But there is something else you can learn from this image too. Look at the upper right of the Hubble image. See all the variations in size and shape of the galaxies there? Look at the same region in the Spitzer image. To Spitzer, they all look the same - similarly sized and shaped blobs. Spitzer's telescope is small (just 85 cm) and the wavelengths of light Spitzer uses are long (comparatively), so the resolution of Spitzer is limited. ( see the advanced page for more information on resolution and associated issues.)

The point of all of this is that some galaxies in the Spitzer images won't look like galaxies. Sometimes Spitzer will just see the nucleus of the galaxy, and sometimes Spitzer's resolution just isn't high enough to distinguish the outer reaches of the galaxy. You will have to go find higher spatial resolution data (often this means optical data) in order to classify the galaxy.

Galaxy archives

Many groups are specifically working to collect images of nearby galaxies with Spitzer. Two such teams are SINGS, The Spitzer Infrared Nearby Galaxy Survey and LVL, the Local Volume Legacy Survey. SINGS is the older of the two teams, so they not only have a website, but also have delivered back to the SSC images of their targets in Spitzer and many other wavelengths. Go here to search the SINGS data.